The Irishman

Bessie was busy gathering all of her family’s possessions and preparing her young daughter and four older boys, including her seven-year-old son Patrick, for their journey. She packed all the necessities and what she didn’t have room for she gave to family and friends. She had gotten word from her husband, Michael Fagan, that he was ready for her and the rest of his family to join him in America. A year or two earlier he had left them behind to go and prepare the way for them – a stressful and exciting time not only for those embarking on their journey but for Michael as well who was waiting for them. The place is County Mayo, Ireland. The year is 1848.

With her five children and all of their worldly goods she made it to the coast and boarded a ship to the United States. The voyages were long and difficult for those with little money and traveling in the confines of steerage where bunk space may have been as little as 19 inches for an adult. The conditions were crowded and lacked proper food and sanitary conditions. The boat made its way to New York City.

Michael met the boat only to discover that his wife and daughter did not survive the 3000 mile, four week long trip and were buried at sea. He took the four boys up the Hudson River and then down the Erie Canal to Utica. He left the boys with his sister, Mrs. George Kelly, and was never heard from again.

What an awful time for the boys – their mother gone and their father abandoned them. Patrick ran away several times, and each time he was found and brought back. The last time he got away he made his way down the Chenango Canal to Binghamton. This article is about my great-grandfather, Patrick James Fagan, and the stories that he told my mother that she passed on to her children.

What an awful time for the boys – their mother gone and their father abandoned them. Patrick ran away several times, and each time he was found and brought back. The last time he got away he made his way down the Chenango Canal to Binghamton. This article is about my great-grandfather, Patrick James Fagan, and the stories that he told my mother that she passed on to her children.

So why did they come to the United States? In 1845 Ireland was struck with a potato blight which decimated their primary source of food. During the next five years over one million people died of starvation and disease in this already poverty-ridden country. More than 1.5 million immigrated to other countries, many to America. Many died of typhus on the “coffin ships” as they came to be called. In 1847 nearly one quarter of the 85,000 emigrants destined for North America died on their voyage.

My sister Joyce, who researches family genealogy, checked “Passengers arriving in New York from Ireland 1846-1851” but found no records to substantiate the above. I suspect records have been lost, weren’t accurate or just haven’t been loaded in the system yet, so the search continues.

I don’t know how old Patrick was when he reached Binghamton or where and how he lived. All that information has been lost to history as so often happens. A 1912 pension record shows his occupation as farmer and shoemaker. Perhaps in those early years he apprenticed to a cobbler? The next time he shows up in family history is in 1859 or 1860. My grandfather tells how his father got married at that time. It lasted one night and they parted the next morning.

My mother held her grandfather in the highest regard. She described him as a “good natured Irishman” with a sharp wit. He was a small man at five foot six and one-half inches. That helps explain why my mother and her sister were so short at about five feet tall. She talked of how he did little Irish jigs and how he always had a story to tell. I am fortunate that I remember some of those stories that my mother passed on to me.

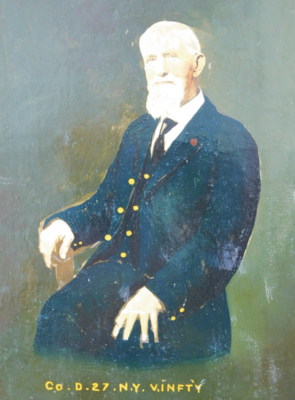

On May 21, 1861, Patrick enlisted into Company D 27th Regiment NY Infantry Volunteers. Regimental history shows they engaged in many battles including both battles of Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. His obituary stated he was in 20 engagements during his Civil War service. On June 27, 1862 he was shot through the thigh at Gaines’ Mill, Va. This did not keep him out of action very long.

Mom told us several stories from this period of time. Patrick told how he and some of his friends sometimes crossed enemy lines at night, played cards and then crept back into camp the next morning to fight another day. I suspect this must have been early in the war when the war was thought to be more of a spectator sport and would be of short duration.

Another story tells how he enlisted with his brother John. They were in battle when John was sent into a house to clear out the rebels and Patrick never saw his brother again. He was presumed dead or taken prisoner. Another version was that Patrick met his long lost brother and they spent the night talking in this house. The next morning Patrick returned to his unit but before his brother left the house it was blown up and they never saw each other again.

About October 1862 the Company Muster Roll shows a name change from Patrick James Fagan to James Patrick Fagan. He told how he changed his name because it sounded “too Irish.” That certainly was an indication of the ethnic bias during that time when the Irish were really looked down upon. He spent the rest of his life as James Patrick Fagan.

On May 31, 1863, his enlistment was up and he mustered out of the regiment. The unit’s history shows that during those two years that 74 men were killed in battle and nearly an equal number, 70, were lost to disease.

On June 18, 1863, he enlisted into Company A 1st Regiment NY Veterans Cavalry. He said he got tired of walking so this time he enlisted where he could ride a horse. For the next two years he saw little action compared to the first two years. He was wounded again, this time at Upperville, Va. on Feb. 20, 1864. He spent nearly one year in hospitals because he was sick. The war ended and he was mustered out of his regiment on July 20, 1865. It is interesting to note that 90 men succumbed to disease, more than the 60 men that were lost in action.

Apparently since he was in the cavalry he was issued a sword. He told how several times he was mounted on horseback and charging the enemy when he barely got his sword up to deflect the enemy’s sword before it decapitated him. How frightening that must have been to see the enemy baring down on you and all you have for protection is a sword in your hand. That sword has been passed down to me and several deep gouges can be seen in it that supports those stories.

We don’t know what he did with his life after the Civil War until he got married on August 30, 1879 to Nancy Marie Tuttle in Great Bend, Pa. In 1880 they had their first child, a boy named Wayne born in Nimmonsburg. In 1882 Lillian was born at Prospect Hill, near Binghamton. A second girl, Florence, born in 1884 at Port Crane. And finally my grandfather, Arthur Lynn was born in 1891 at Church Hollow near Coventry.

In 1911 he and his wife were living at and employed at a place called “The Pines” on Fairview Avenue on the north side of Binghamton. They had taken in a young boy that was afflicted with tuberculosis and cured him. This story appears in a newspaper article during that time. He retired in 1920 at the age of 79.

James died in 1938 at the age of 97. He spent his last nine years living with his daughter Lillian at Hunt’s Corners near Lapeer. He was the last of Broome County’s Civil War soldiers. His pension records show his occupation as farmer. Considering how often he moved during his life I don’t think he ever actually owned a farm but instead was a farmhand. Since his arrival at Binghamton around 1850 I don’t think he ever strayed far from Broome County.

I have seen pictures of him in his older years when he had white hair and a long, flowing white beard. The last story my Mom told of him was how he liked to challenge young boys to just touch him with a stick. By then he was carrying a cane. Every time the boys tried he would knock their stick away with his cane. He attributed this skill to his time in the Civil War when being adept at handling a sword meant the difference between life and death.

A while back we visited his grave in Harford Mills Cemetery in Harford Mills, just west of Marathon. He and his wife are on the same granite marker as his daughter Lillian Boice and her husband. Nearby is a veteran’s marker inscribed with the two regiments that he so proudly served under for his country. I wish I had had the privilege of knowing him myself.

I would like to thank my sister Joyce for the family genealogy that she did for so many years that helped make this article possible.

February 19, 2020